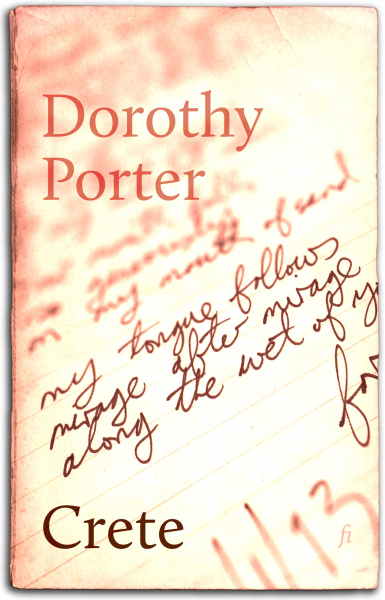

Crete

Crete

by Dorothy Porter

published 1996

Ligature

finest

genre Poetry

The follow-up to the international bestselling The Monkey’s Mask, Dorothy Porter’s Crete is an astonishing collection that traverses Greek myth and Russian poets, the memory of cigarettes and the wild abandon of love.

Crete is a heady mix of dark humour, archaeology, breathtaking eroticism, risk-taking and effortless economy. It is a book by a writer at the peak of her highly original powers.

This collection includes 81 poems in six cycles:

Crete (Parts 1 and 2) · The poet and her lover travel to the ancient island and find it full of echoes, old myths and modern worlds overlapping. From the untranslatable language of Linear A to a tropical bikini top, each of these poems is a thread, a labyrinth, and a Minotaur.

This Weird Solidarity · A haunting series of fragments showing glimpses of the key poets of the Russian Revolution — Mandelstam, Pasternak, Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva — and the brief and lasting connections between them.

Missolonghi · Lord Byron reflects on what might be his last, unrequited love, shortly before his death in the midst of the Greek War of Independence.

Bone-Burning Tunes · Thoughts of past and future are overwhelmed by a consuming and ecstatic love.

Cigarettes · Vignettes of cigarettes — sharing them, remembering them, the stale and the sweet, a perfect moment, a torture.

Summer 92 · Love poems, including for the first time handwritten drafts of the poems “Drought Sonnet”, “Perfume and Drowse”, “My At-Last Lover” and “As Cunning as Serpents”.

“The ‘Crete’ sequence is quite demanding, in an intellectual sense, but it’s suffused with feeling. It demands a lot of readers in that it requires background knowledge, and the poems make a lot of weird juxtapositions and jump and leap. They’re clearly written, but I think it was one of the hardest books to write.” — Dorothy Porter

“Contemporary readers are transported by Porter back to an era of goddesses, bull-men and bull-leaping, of libidinal honey, of purple grapes, of octopuses, snakes, labyrinths, and volcanoes. However, beyond the lush, celebratory lyricism, we are also prompted to consider the progressively urgent ethical questions asked by the poet concerning the violent, spectacular art of Crete’s ancient past, and the ethical status of art more generally.” — Lyn McCredden, Journal of Australian Studies